The process of informed consent is really important in socially engaged practice – this gives participants the right to change their mind and withdraw consent at any point.

I haven’t had people pull out of my projects many times before – ideally, we will have built up lots of trust along the way and I will have responded to any concerns which crop up – but it does happen occasionally.

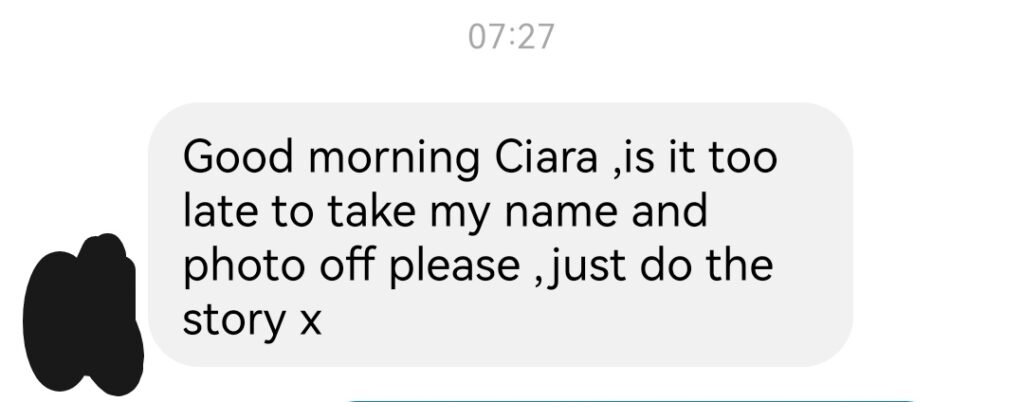

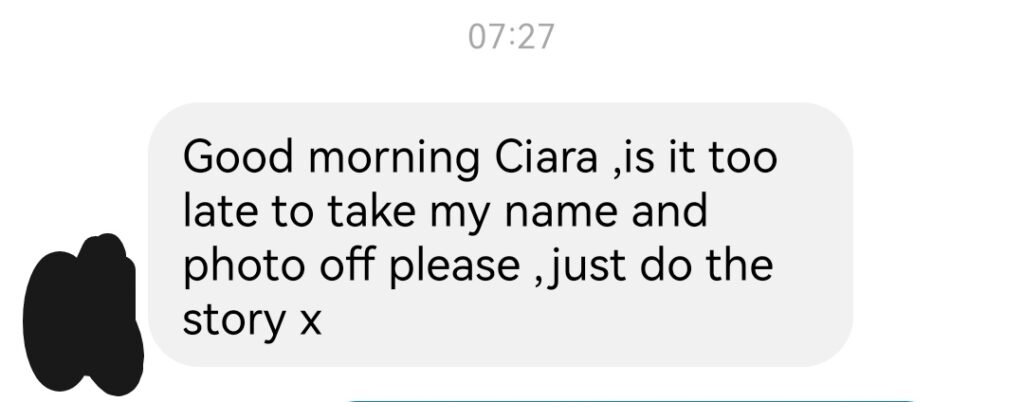

This morning I woke to the kind of message I dread from one of my Reflections participants: “Good morning Ciara, is it too late to take my name and photo please, just do the story”.

This is a disappointment to me – because I happen to love the portrait I made of this participant, who was one of only a handful so far who had been willing to show their face – but it’s not the end of the world. Their words remain very powerful and they are willing to let me use their voice, which I have recorded and turned into short audio clips. I have alternative images to use alongside their words, which are non-identifiable.

The egotistical photographer within me wanted to use the beautiful portrait, but I’m having to remind myself that this process is not about me. A consent form is in some ways a starting point – the relationship of trust which I create with participants is far more precious and something I view both as a privilege and responsibility.

I have worked with Gypsy and Traveller community members before but never in this socially engaged way – where I’m working one to one with individuals over periods of many months, and talking in-depth about their personal experiences.

My previous work (from 2009-14) was documentary – I mostly tagged along to family events and had conversations along the way. That work was independent and self-funded – and there was none of the baggage of exhibitions and archives and local authority power dynamics attached.

Perhaps people back then were also more trusting of the camera – I feel the explosion of social media in the past decade has made everyone much more wary these days, including members of these communities. After all, the mainstream representation of these groups has always been – and continues to be – extremely negative. Who could blame the majority of individuals for being wary of nosy outsiders and their cameras?

During the Reflections project so far, I have had many ups and downs. I’ve had numerous introductions to and conversations with people which have ultimately gone nowhere – but which all added to my understanding of people’s experiences of the recent past.

I’ve worked intensively with five participants so far and hope to connect with one or two more before my engagement wraps up this summer. But it’s been challenging at times to pin people down to visits – life gets in the way for people (myself included) and I’m mindful that I’m working with people who have, frankly, a lot more important things going on. There have been extended hospital stays, deaths in families and other emergencies, along with childcare responsibilities and family holidays.

I have also had concerns to allay about who will see the work and how to protect participants’ identities – this seems to sometimes be as much to do the internal gaze (what other community members may think) as the external gaze. There are sensitivities and complex dynamics around this work that I may never fully understand but I’m doing my best to represent people in a way which feels comfortable to them and true to their experiences over recent years.

Work I’ve produced during the past year with women from the Traveller community is now on show at Open Eye Gallery, where it will be until 23 December, and it looks brilliant. Our work is only a small part of a much larger showcase of socially engaged projects – it is in the atrium area outside the gallery along with the other two Reflections commissions by Tadhg Devlin and Sam Ivan. Inside are another three fabulous projects from different areas of Cheshire and Merseyside.

Work I’ve produced during the past year with women from the Traveller community is now on show at Open Eye Gallery, where it will be until 23 December, and it looks brilliant. Our work is only a small part of a much larger showcase of socially engaged projects – it is in the atrium area outside the gallery along with the other two Reflections commissions by Tadhg Devlin and Sam Ivan. Inside are another three fabulous projects from different areas of Cheshire and Merseyside.